Review: “Mary Jane" at Three Bone Theatre

The titular character, played by Nonye Obichere, carries the weight of parenthood and disease; however, the fabulous Obichere doesn't have to carry her strong supporting cast.

In her New York apartment, Mary Jane (Nonye Obichere) cares for her 2 1/2-year-old special needs child. Thrust into difficulty, she finds a wellspring of optimism in her deep love for her son Alex.

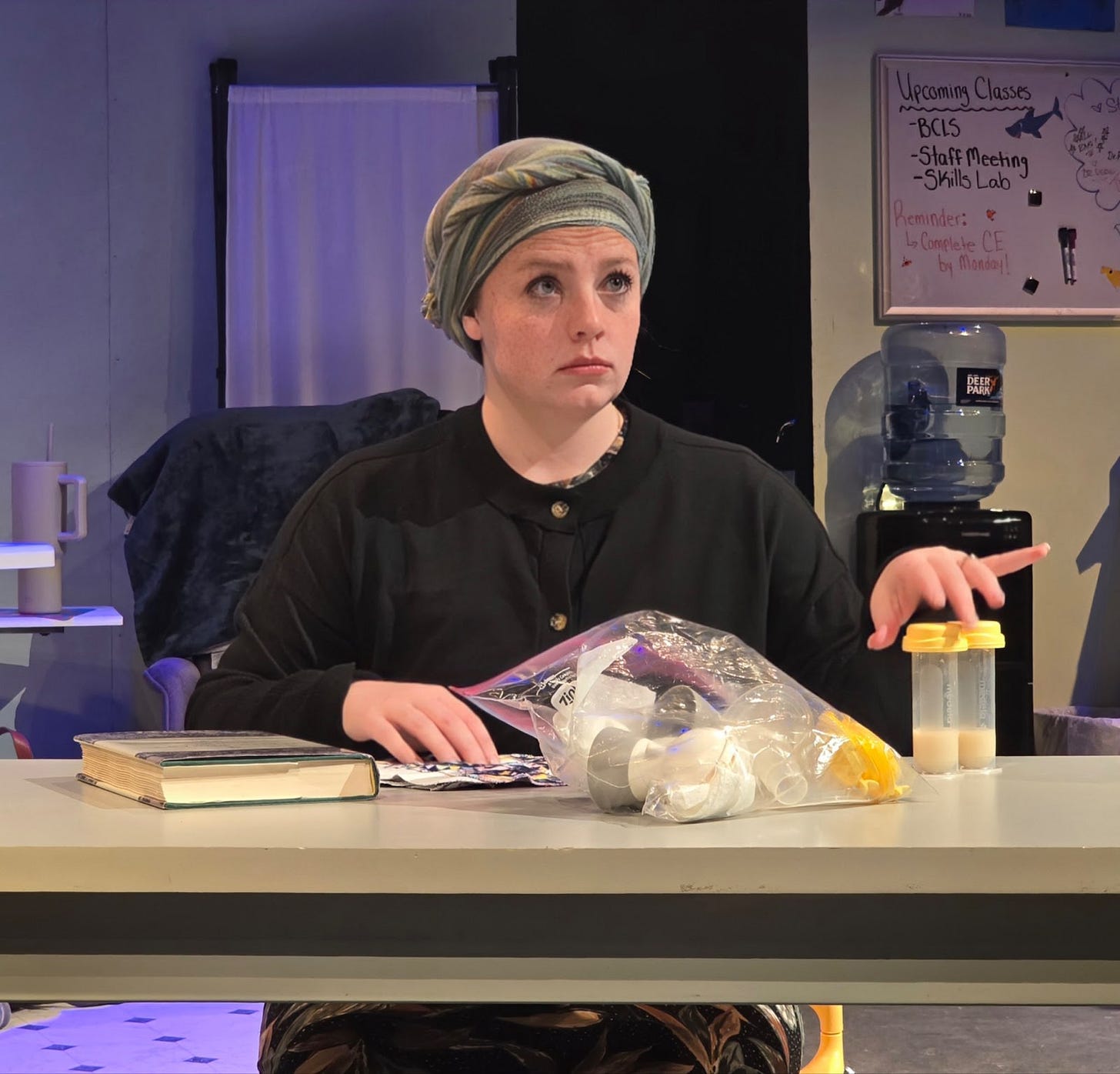

We only hear from her son Alex when a beeping alarm blares warning of a problem with the medical apparatus keeping him alive. It makes sense that we never see him on stage: Mary Jane is a story about the intra- and interpersonal lives of women. Evidence of him is everywhere on set though, from medical care devices washed in the kitchen sink, to little children’s clothes folded on the couch, to enrichment toys collected on the floor.

“Mary Jane” at Three Bone Theatre

February 7-23

Written by Amy Herzog

Directed by Robin Tynes-Miller

Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays at 8 PM ET

Sundays at 2 PM ET

Performances held at

The Arts Factory at West End Studios

1545 West Trade Street

Charlotte, NC, USA

This is the backdrop for the stuff of the play at Three Bone Theatre: a series of conversations between Mary Jane and the women who support her. Home nurse Sherry (Lisa Schacher) shows a deep sense of duty to both Alex and Mary Jane, insisting upon sleep for Mary Jane and raising her hackles at the tale of Donna, another home nurse who underperforms when on duty.

The apartment building super Ruthie (Banu Valladares) is concerned with Mary Jane’s body, the trauma it absorbs, and the implications that might carry for cancer. Later, at the hospital, mother of seven Chaya (Maci Weeks) provides commiseration, and we realize that Mary Jane, no matter how surrounded she is by support, feels absolutely lost.

Mary Jane is positive to the point of raising an eyebrow. She sets a sunny tone in each conversation in the first half of the play, making space for her counterparts and finding sweet humor everywhere. As she slowly shows us the hidden depths of her feelings, Mary Jane’s declarations of goodness and patience, and then her fragmented memories stated aloud, start to look like the tips of icebergs.

However, Obichere’s performance goes beyond the chipper surface. She drops her face into a dead-eyed, thousand-yard stare when Mary Jane isn’t focused on being encouraging to herself and others.

Only when she realizes she has zoned out does she snap back to her cheery self. Where within her does such generosity cease to be a genuine response and instead become a screen blocking her own pain?

The hallmark of the writing in Mary Jane is the subtle but overarching hyperrealism of Amy Herzog’s script. Seeking a natural conversational cadence, Herzog and director Robin Tynes-Miller dive into the long one-on-one conversations with interruptions, talking over each other, mutual laughter at misunderstandings, and forgotten points. The naturalism is performed well in this cast, and lulls the audience into a space where it is unsettled by the subtle yet striking unrealism that appears.

Herzog uses the natural dialectic landscape to surprise with small shocks — the misunderstandings are polite but occur regularly, the disagreements are firm to the point that they feel harsh, and moments of shocking candor pass without offense as long as the offending character says, “if you don’t mind me saying” first.

Speaking to Tenkei, the hospital chaplain (Valladares), Mary Jane is surprised to learn she was raised Episcopal but became a Buddhist nun just seven months earlier. “Doesn’t that … forgive me, Tenkei … doesn’t it make your life seem kind of arbitrary?” Mary Jane asks. “It’s not the only thing that makes my life seem arbitrary,” Tenkei replies.

The supporting characters are designed intentionally by Herzog, eight dual roles played by four supporting actors. The landlord and the chaplain (Valladares), and the home nurse and the doctor (Schacher), represent authority and care. Schacher projects the naturalism of Herzog’s writing effortlessly.

Cate Jo appears as the delinquent music therapist who cannot see the impact she has on her patients, as well as Sherry’s niece Amelia, who comes to meet Alex but just doesn’t quite understand the reality of it despite her best intentions. Maci Weeks is strong as Chaya, who endures the difficulty of grappling with the hospital system with a grim acceptance, and even stronger as Brianne, a mother who is only just beginning to understand the challenges presented by the bureaucracy she must navigate for her child.

Obichere delivers the substance of Mary Jane’s conflict artfully. While confronting the complexity of raising Alex with love and care, Mary Jane has not considered the psychological toll exacted in the background. In two crucial moments of recall — one where she remembers that she once was a person who would get high and hike in the mountains, and another when she forgets that her sister sent her cookies once a month for a year — Obichere shows us that Mary Jane’s bandwidth is overloaded, and she is worried her mind may be in shambles.

It has been almost three years, and she is only beginning to process the changes her life underwent after she gave birth.

RJ Evans’s sound design is evocative and bold, underscoring the tension between sanity and disintegration that Mary Jane experiences. Kel Wright’s dreamy, broody lighting choices highlight Mary Jane’s moments of solitude, and are rooted in her complicated relationships with migraines which she both dreads and finds beautiful.

With excellent performances from the Nonye Obichere and her supporting cast, Mary Jane gives the audience many rich themes to explore, including the unspoken traumas of motherhood; the confusing, unsustainable state of healthcare in the United States; and the heavy burdens that weigh us down, making change hard (if not impossible). You can watch Obichere’s eyes convey what’s going on in her character’s mind, as her face becomes the visual representation of an internal monologue as fraught as one from Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway.

Unlike Clarissa Dalloway, however, the women of Mary Jane have no safety net and no lavish parties to save or distract them from reality. Herzog’s script feels even more bleak with the knowledge of the author’s own experiences caring for a terminally ill child.

Although we leave her as she descends into the darkness and pain of a migraine, there is still hope for Mary Jane. The connections large and small that she’s able to make with other women may just be enough to weave a community and a safety net of her own if she’s able to navigate her trauma.

Mary Jane runs through next Sunday, February 23. The play contains some adult language, difficult conversations related to illness and caregiving, and descriptions of chronic illness in children. Recommended for ages 14+.